Originally published December 1996, volume XXI number 131 by Jim Moodie

Ann and Carl Beam’s Top 10 Reasons:

- A healthy alternative to building with trees.

- Do-It-Yourself – Anyone can work with it

- Aesthetically pleasing and long lasting.

- Environmentally friendly

- Waterproof

- Termite proof

- Soundproof

- Easy to make

- Safe – Fireproof

- Dirt Cheap

Nothing prepares you for the home of Ann and Cark Beam. The two visual artists called West Bay, Ontario, on the north shore of Manitoulin Island – a triangular extension of the Niagara Escarpment that rises from the waters of norther Lake Huron. For all of Manitoulin’s surprises – its sheer size, for one, not to mention those curious outcroppings of limestone – the island is, above all, a pastoral northern Canadian habitat. Long barns and weathered shake houses punctuated its 150-kilometre length. Separated by miles of rocky pasture, the communities – some native, some white – cling fiercely to their distinctive terrain as well as to their hockey rinks. And wherever you are on one of the straight two-lane hard-top roads that weave the communities together, you’re liable to come across someone hauling firewood out of the bush-in just about any season.

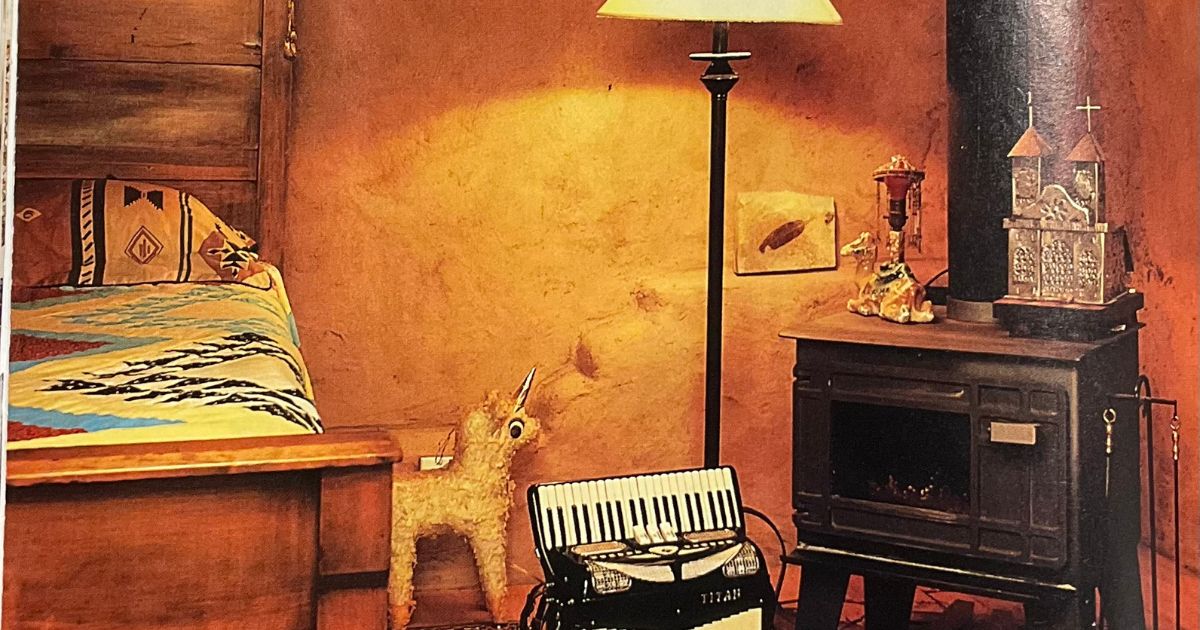

Inside and out, this northern Ontario adobe abode is unique, just like Ann and Carl Beam, the artists who built it.

In Ann and Carl Beam’s part of Manitoulin, the waters of West Bay lap against the edge of town. There’s no town-centre in the village, unless it’s the intersection where the gas station is. And most folks live in modest frame houses, each wood-sided bungalow virtually indistinguishable from the next. Indistinguishable, that is until you get to the Beam place. Even from a distance, you can see that something is going on there in that pine-curtained piece of property a country block in off the two-lane highway. Something bold, mystifying and well, pink. Salmon pink.

There are three buildings on the property: a main house, a guest house, a studio. All are compact, boxy and carry an almost unavoidable flavour of the American Southwest. Wood lintels grace the doors and windows. Striking log vigas, or round beams, protrude from the guest house and studio. Decorative touches evoke a warm, arid atmosphere – things such as the bleached animal skulls and chile-pepper ristra, the undulating wing wall in the courtyard (which also acts as a buttress), and the dome-shaped horno, or outdoor bread over, arching chest-high in the yard. What are adobe buildings doing here in northern Ontario? You have to know the builders.

Born in West Bay, Carl, a rugged intense individual, has always reached beyond the perimeters of his home community. His sculptures, pottery and painting incorporate numerous influences and media; a typical photo etching might mix such seemingly disparate images as a group of native hunters with Martin Luther King Jr. His wife and fellow multimedia artist, Ann – a slender woman whose soft-spoken manner belies a thoughtful, determined spirit-is originally from the United States. And it was there, during an extended period the couple spend in an area north of Santa Fe, New Medico, that the Beams first encountered the adobe material with which they would eventually build their strikingly original home.

At the time they acquired the Manitoulin property, the two were sharing a cramped house in the Ontario city of Peterborough. Carl’s grandfather had passed away and left him a stretch of heavily grazed pasture in West Bay. Ann and Carl decided to move to the island and build. At first they flirted with the idea of building with wood, but then they remembered their New Mexican dwelling and committed themselves to what is arguably they oldest and least wood intensive form of house construction in the world.

Adobe. The word conjures up many images – dusty pueblos, cramped Middle Eastern villages, windswept mesas, sagebrush speckled hills. It is one of those words that almost everyone has a strong urge to say aloud, even if they don’t know precisely what it means. Adobe carries a distinctive early connotation.

As well it should. Derived from the Arabic al-tob, adobe is a Spanish word that in English means, simply, “sundried mud brick”. No longer the building material of peasants, adobe is enjoying renewed interest across the continent, and people are building fine, elegant, ambitious home with adobe bricks. According to Michael Moquin, who edits a magazine called the Adobe Journal-its a substantial, New Mexico-based publication, and a testament to the material’s current (and frequently upscale) appeal-most adobe houses now built in the United States are large custom homes in the 2,500 to 4,500 square foot range.

Still, one doesn’t picture adobe anywhere north of New Mexico. Can it really be practical in northern Ontario?

The Beams insist it is. furthermore, they see earth block as the perfect alternative to such sesource gluttons as wood, and subh high-“embodied-energy” (the energy consumed in manufacturing) products as regular brick. And being artists, the idea of breaking boundaries comes naturally.

For Carl, being a pioneer offers only so much gratification; he along with Ann, would prefer that other Canadians benefit from what they have learned; namely, that by using a slightly bigger black than is used in Southwest, adobe can be easily adapted to our colder temperatures, as well as made waterproof through a very simple process during preparation. “I hope these things will make more sense to people as time goes on”, says Carl. “See, that’s part of our goal, to see that happen”.

To the Beams, the formation of an adobe block is about as complicated as, well, having fun at the beach. “Ill tell you what”, Carl explains. “Everybody’s done this- you put wet sand in a pail on the beach, then turn it upside down and pull the form off”

Well, maybe it’s not quite that easy. But it’s surprisingly close.

Adobe actually does consist largely of wet sand, with a dash of clay thrown in for plasticity.. To this mixture as it standard in contemporary adobe construction, the Beams added a stabilizing (waterproofing) agent known as asphalt emulsion- a liquid mixture Carl likens to a milkshake, in that the asphalt is not full dissolved but simply suspended. The breakdown, roughly stated, is: 9% clay, 86% sand (including both fine and coarse particle) and 5% asphalt emulsion. The traditional adobero mixed his clay and straw by hand, blending it in a pit with a shovel and hoe; the Beams opted for a gas cement mixer. With its 9-cubic-foot capacity, “we could make about 22 blocks at a time” says Ann. “On a good day, with a crew of just myself, Carl and one helper, we might make a total of 300 blocks. But it’s beautiful labour, and I never felt bad about how hard it was.”

A FEW DIRTY SECRETS

Ann and Carl’s recipe for the perfect adobe block

- 1 part clay

- 9 parts sand

- 1/2 part asphalt emulsion

- enough water to make a stiff mixture

Sand should also consist of both fine and coarse particles (a mixture of about 50-50), with the largest aggregate measuring no thicker than 1/4″ (it should not be like gravel). Your best best will probably be to talk to your local aggregate-supply company.

Most stock several grades of sand.

Clay should be pulverized beforehand to blend nicely in a mixer (the Beams ran it though a wood chipper).

Asphalt emulsion (60% asphalt cement, 40% water and chemicals to make it binding), the stabilizing agent needed to waterproof your adobe blocks, comes in a liquid form, It is available from McAshphalt Industries Limited, 8800 Sheppard Ave E, Scarborough M1B 5R4; (416-281-8181).

After the adobe is mixed, it is poured into deep, wooden, ladderlike forms, open on both the top and bottom. The Beams lined their forms with sheet metal so the bricks would be easier to remove, though they admit that painting or oiling the sides would be just as effective. Traditionally, the bricks are poured straight onto the ground, but since the Beams’ field wasn’t flap as the ones found in the Southwest, the couple made a plywood base for their forms. After the forms are pulled off-almost instantly the bricks need about 3 weeks in open air to fully cure.

While the dimensions of adobe blocks vary from region to region, a typical block in New Mexico would measure 4″ x 10″ x 14″. To reduce the number of blocks they’d need to make, the Beams elected to go slightly bigger with a block measuring 4″ x 12″ x 16″ that weighs approximately 40 pounds when dry. It took about 3,000 blocks to build the main house.

The actual laying of an adobe wall, according to the Beams, is straightforward. The blacks are wheelbarrowed or trucked to the construction site then bedded in a “mud” mortar of the same adobe material, with 1/2″ gap left between bricks. Subsequent courses of blocks are staggered, over lapping the ones below by at least 4″. Standard masonry lines and vertical poles set at each corner keep the walls in line. Walls can go up quite fast, the Beams’ studio a 22-by-38-foot building, went up in just 10 working days in 1994. (They built the house over a six-month stretch back in 1992).

The results are building of considerable strength, which was proved when the Beams took a few of their blocks down to New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, in Socorro, New Mexico, for compression testing. The code for adobe bricks in the Southwest is 300 pounds per square inch; the Beams’ black measured 450 pounds per square inch.

“We knew the blocks were good but just wanted to see for sure”, says Ann. “We passed with flying colours”.

The Beams have stuccoed most of the interior and exterior walls but for now have left the house’s south-facing exterior wall un-plastered. Many adobe builders choose to stucco the walls even though it’s not strictly necessary if the builder adds asphalt emulsion to the adobe. The use of stucco has made it hard to instantly recognize a building as an adobe structure; Carl points out that when he and Ann first moved to New Mexico, “we were living in an adobe house without even knowing it”.

Neither have they felt the urge to add insulation to the walls. The Beams, who heat their home with two wood stoves, claim to have never experienced a moment of discomfort. It’s warm in the inter, and cool in the summer” is Carl’s stock answer. Stock maybe, but not glib or unfounded. Other adobe dwellers have been making the same observation for centuries. And recent studies have borne this out; although adobe has been assigned a very low R-value, it has also been scientifically shown to have excellent heat-storage capabilities.

According to George Austin, a geologist with the New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, adobe has “often been unjustly maligned because on R-values (resistance to heat transfer) were considered when evaluating thermal performance. “However, when assessed in terms of its “effective U-values,” which take into account a building’s capacity to hold heat, adobe scores much higher. In practice, reports one study, the earth block will store heat during the day and then convey this warmth inside a night. “This cycle is repeated in what is known as the flywheel effect”, the report explains, “and is responsible for the comfort level well known to those who inhabit properly designed adobe homes.”

As far as testing this formula in the north, the north, the Beams are not the first to do so. In the early 1800s, a number of large adobe homes were built in New York state, as well as in the Toronto area. Vera Stoddart, who lives in a 166-year-old true adobe farmhouse made from clay and straw mixture near Bradford, Ontario, has documented 16 other such buildings in her area, 10 of which are still standing. Hers is “a good solid house”, she remarks, one that requires neither air conditioned not additional wall insulation. When it comes to design, the Beams say they opted for simplicity. “We did not want something that looked like it just came out of New Mexico, that looked too quaint,” explains Carl. “We decided to go with a look of just square boxes, basically”. For all the creative embellishments the couple have made, both inside and out, one is never able to forget the earth wall itself-neither its frank, natural beauty not its practical advantages. It’s affordable (the Beams spent only $50,000 on their house). The walls, says Ann, not only block out microwave transmissions but draw moisture out of the air. “Anyone with arthritis says they’re really comfortable in an adobe house,” she explains. Furthermore, as Carl is anxious to point out adobe is not only sound proof but also termite proof and most importantly, fireproof.

“The construction of earth housing would avoid a lot of needless deaths that occur in frame houses,” Carl says. “In the process, we would be saving thousands of trees.”

There is wood in their building of course. “At least it’s featured,” Carl points out, “not buried as some structural unit in the wall.” Even with their use of wood lintels and square beams and vigas, the couple estimates they have spared between 80 to 100 trees by building with adobe. Whis is as good a reason as any other, they fugure for giving mud brick a chance. This , plus the fact that adobe also just happens to look and feel and linger like a piece of the earth itself.

GETTING DIRT ON ADOBE:

Here are several sources of Adobe Info:

- Adobe and Rammed Earth Buildings: Design and Construction, by Paul Graham McHentry Jr., University of Arizona Press, 1989

- Adobe, pressed-earth and rammed-earth industries in New Mexico (revised edition), by Edward W. Smith and George S. Austin, New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Minerals Resources, Socorro, New Mexico, 1996

- Adobe Journal, Box 7725, Albuquerque, NM 87194; (505) 243-7801

- Southwest Solaradobe School, Box 153. Bosque, New Mexico 87006; )506) 861-1255

- New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro, New Mexico 87801; (505) 835-5011