Flames of a bonfire light up the white faces in a crowd rallying in a Châteauguay, Quebec, parking lot, where an effigy of a Mohawk Warrior is burned in these nightly protests. Police clubs and tear gas are required to turn back 7,000 angry citizens. Another mob mercilessly stones a convoy of cars leaving the Kahnawake Mohawk reserve with women, children and seniors present. Motorcycles roar as these suburban commuters chant in French for the government to break down the Mercier Bridge barricades that prevent them from getting to their jobs in Montreal.

This is the summer of 1990, when the Oka Crisis brought the world’s attention to Canada and our unsettled relationship with the Indigenous population. The global news now includes us in its ABCs of street violence: Azerbaijan, Beirut and Châteauguay.

The Warrior Society that infuriated those suburban commuters was formed here in 1971 and uses roadblocks to defend the rights of the Mohawk people.

I approach the bonfire cautiously with my camera, fully aware that, as the English-speaking media in this French-speaking rally, I am also a target of their rage, since our coverage has been sympathetic to the Mohawks. I click a couple of frames, then quickly change locations. Suddenly, beside me, a fight breaks out. The adrenalin is palpable. Arms reach in to break up the two burly men as my camera flash lights up the scene of mass frustration exploding. I tuck my equipment to my chest and duck through the pressing crowd.

The Oka Crisis of 1990 left one person dead, several men in prison, and communities scarred. But 30 years later, on a somewhat positive note, it is remembered as a turning point for Canada’s Indigenous population. In the face of blatant racism and intolerance, the Mohawks stood united and publicly demonstrated a bravery that resurrected a latent resolve for their ancestral role as the protectors of the land. Those tumultuous times awakened youth to their cultural heritage—some had never even heard of the Great Law of Peace—and brought to public light the great divide that has existed in Canada since colonization.

The riots took place in the region I covered as a weekly newspaper editor. The barricading of the commuter bridge by the Mohawks of Kahnawake was an act of solidarity with another Mohawk community where the conflict began, Kanehsatake, within the town of Oka.

The Mohawks say the conflict actually began 300 years ago. It’s about land that they never ceded. The laws they had in place pre-contact—that is, before the Europeans came—should prevail over Canada’s rule of law, they say. Oka was founded by Sulpicians in 1721. They were French missionaries who converted some native peoples to Christianity, even one who would later be made a saint, Kateri Tekakwitha. An Algonquin-Mohawk born in 1656, Tekakwitha lived at the Jesuit mission in Kahnawake. In 1893, Trappist monks, also from France, established the famous Oka cheese factory. Then, 97 years later, it was the French again: Mayor Jean Ouellette and the Oka town council planned to bulldoze a grove known as The Pines and expand the municipality’s golf course.

The Pines are a sacred burial ground for the Mohawks, who began a peaceful protest at the site, with citizens marching alongside them with signs in the streets. The media showed up. Then the provincial police, Sûreté du Québec (SQ), showed up. Their SWAT team stormed in with tear gas and military weapons. The reporters and photographers were in the line of fire and captured video footage showing the chaos that erupted. Shots were fired from all sides, and Cpl. Marcel Lemay of SQ was killed.

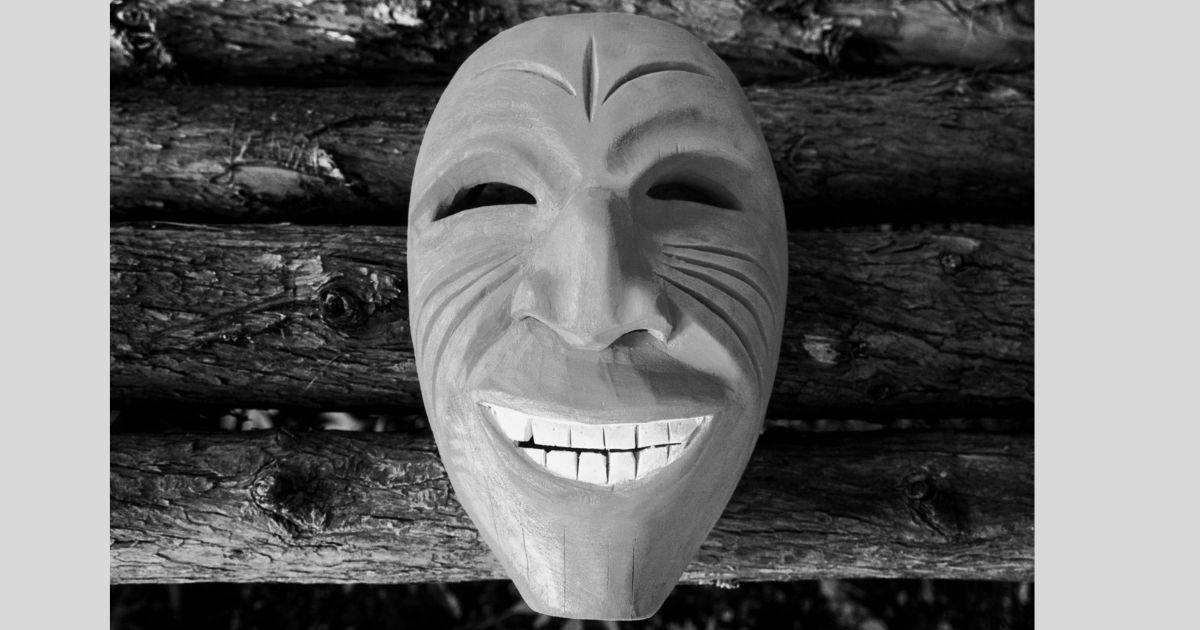

Montreal Gazette photographer John Kenney was there and took the iconic photo of a masked Mohawk Warrior standing atop a rolled-over police vehicle with his rifle raised. They had won the battle that day, on July 11, 1990, in a standoff that would drag on 78 days into September. Kenney recalls that, after the shootout and the smashing of police cars, he took no chances of getting his photos confiscated by Warriors who didn’t want to be identified, so he stuck the rolls of film inside his socks.

“There was one incident,” he says “… when the army brought outside media in for a ‘close-up’ look at the Mohawk position. They were brought directly across the two-lane Highway 344 from the entrance of the treatment centre, [and] I was able to throw some canisters … to a Gazette reporter.”

Shaney Kumolanien was another photojournalist on the inside of Kanehsatake all summer. Her photo of a soldier—stern faced, nose to nose with a masked Warrior—became the emblem of the crisis. Readers could put themselves into the boots of each man and sense it from opposing perspectives. Did each believe their cause was morally just? To many, it was a clear-cut case of Mohawk aggression and civil disobedience and the government should enforce our law and take control with a heavy hand. Others recognized the injustice against the Mohawks, who were abiding by their hereditary law and required to take up arms to defend their home and native land.

Back in Châteauguay, across the St. Lawrence River from Montreal, the military-savvy Warriors cut tank traps into Highway 138 and parked vehicles across the four lanes. They used a giant mirror to reflect the sun into the eyes of the police as each side stared back at each other throughout the long hot summer. Police came from all over the province to work shifts armed with Canadian Army C7 assault rifles at the barricades, and directing traffic while eating a Popsicle. It was an odd scene in an otherwise ordinary small city: children on bicycles and curious pedestrians bringing lawn chairs and portable stereos to the barricades, yet with the constant uncertainty that something might burst the tenuous peace.

In mid-August, the Quebec police yielded to the Canadian Armed Forces. Soldiers and armoured vehicles rolled into both towns: Châteauguay and Oka. For the residents, it felt like a true war zone with helicopters patrolling overhead. My dentist, who lived along the St. Lawrence River, ran humanitarian food deliveries in his pleasure boat around the army to the reserve. Local church ministers got inside the Mohawk communities to act as observers and human shields. At the highway, the army set up a stricter perimeter with razor wire to keep the onlookers at a distance. By this time, media from around the world were here on a daily basis to cover the standoff. For the local newspaper, a global story had landed on our doorstep.

Brenda Castonguay, a young woman working at a 1-hour film-processing store just down the street from the barricades, wound up having a prominent role developing the film for the professional photojournalists. Among them was legendary Toronto Star photographer Boris Spremo, who inspired her to study photojournalism and pursue her own career with a camera.

Kumolanien says that summer definitely launched some careers. Those who stayed to cover the front lines produced incredible images. A picture by Ryan Remiorz ran in publications everywhere showing Waneek Horn-Miller dragged down by soldiers with her tiny sister clutching her in terror as they attempted to walk to safety out of Kanehsatake before the army stormed in. Horn-Miller went on to become an Olympic water polo athlete for Team Canada and a motivational speaker. In 2005, she accepted my invitation to the Châteauguay high school where I worked on a student newspaper; there, she showed the students her scar from the bayonet that nearly pierced her heart.

“The military were put into the middle,” says Kumolanien. “I talked to one major; they felt used.”

Photojournalists who cover these hot situations realize that all of the stakeholders, the actors in these dramas, are just people. The soldiers and the police are doing their jobs, following orders. At the most recent confrontation in Tyendinaga, Ontario, which shut down Canada’s railways in March 2020, a Mohawk woman shouted across the tracks and named individual Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) constables who she knew in the community. Enemies now on the international stage, they could have exchanged friendly greetings at the grocery store the previous week.

I asked Kumolanien her thoughts on the blockades, then and now, and changes during the 30 years since Oka.

“Until 1990, I barely knew of native issues,” she says. “My first thought relevant to recent protests is about the racism and general clued-out-ness of many Canadians, and how it was used and spurred on by politicians. As far as my photo, there’s something to the fact that it’s still relevant to current events, that the tension between First Nations and the Canadian government wasn’t resolved. The lack of trust, neglect continued. Governments mostly tried to rebury what wasn’t simple to resolve.”

Kumolanien points to the creation of Nunavut as a victory. In 1999, it became a Canadian territory from an Aboriginal land claim agreement with the Inuit people, the first in the Americas to achieve self-government.

“Maybe it’s a living experiment as well in reversing colonialism?” she says, equally realistic that power struggles can arise from within. “We can’t fall into the ‘noble savage’ trope either. There are some self-serving Warriors out there. Profiteers with tobacco and drugs, et cetera. In May 1990, there was a shooting in Akwesasne [another Mohawk reserve straddling the borders of Quebec, Ontario and New York]. SQ, OPP, NY State Police and army all involved. Lots of media for a week.”

That conflict was internal. Mohawks on the U.S. side had casinos and bingo halls, and others were trying to shut them down. Within all of the Indigenous communities, there are different points of view and politics at work. Struggling with high unemployment, lack of infrastructure, and drug and alcohol abuse, many are willing to sacrifice the old beliefs and strive for a better quality of life. Who has the final authority is never quite clear when you have the democratically elected band councils and the elders and hereditary chiefs and, for the Mohawks, the traditional clan mothers and the longhouse ceremonies.

Joseph Tokwiro Norton is the grand chief of the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke in 2020 and was grand chief in 1990, too. He gained respect from all sides of the negotiations back then, as well as during the recent standoff, and leads them with tolerance and understanding. In the meantime, since being the familiar voice for his people during Oka, he transitioned into a highly successful internet business life in online gambling. The company made $4 million in 2002 and created jobs.

Equally inspiring is Silver Bear, Stephen Kateroton McComber. He has been a prominent keeper of Mohawk tradition in Kahnawake as a sculptor, dancer, public speaker and now gardener, teaching how to grow and save seeds of the Three Sisters—corn, squash and beans. His efforts to popularize his community’s spiritual side have paled beside the traffic that pours in for cheap cigarettes and cannabis. But he has been a force for healing since 1990 and creating a cultural bridge between Indigenous and non-Indigenous neighbours. He spoke at a large gathering in 1995, where citizens of Châteauguay came to Kahnawake for a “peace exchange” organized by the two towns’ chambers of commerce.

As Thanksgiving approaches, we remember that it was a time when European settlers and native North Americans united and shared the bounty of harvest time. It is a Haudenosaunee law to give thanks to everything in the natural world and remind human beings of our relationship and responsibility toward all of creation. This is the fundamental message that our Indigenous people try to convey during times of conflict over land and water threatened by development.

Since Kanehsatake/Oka in 1990, there have been other standoffs: Gustafsen Lake, Burnt Church, Listuguj, Ipperwash, Six Nations, Standing Rock and now the crisis on Wet’suwet’en traditional lands.

Last March in Tyendinaga, where the Mohawk Warriors set up the rail blockade to support their Wet’suwet’en brothers opposing the development of a natural gas pipeline, spirits were low after the OPP had hand-cuffed and arrested 10 protectors. People from the Mohawk community began arriving to stand strong in front of uniformed constables with many vehicles, a surveillance drone and a circling helicopter. Suddenly, breaking the uneventful stare-down, the people began yelping and leaping out of their vehicles and pointing to the sky. A bald eagle, their most sacred symbol of spirituality and strength, circled overhead. It was a sign that their cause is just, even amid a society that may never truly understand.

Phil Norton has been seeing life through a lens for over 40 years and working professionally as a writer and photojournalist. He freelanced for Harrowsmith and Canadian Geographic Magazines on environmental and outdoor adventure topics, and served as the editor of a bilingual weekly newspaper, The Huntingdon Gleaner in Quebec, and ran the stock photo department for The Montreal Gazette. Later, in Quebec, he shared his experience in high schools leading students on community photo shoots for publication.